As an African-American woman with an unusual name (Dara Tafakari), I know all too well that America is unkind to difference. People have always butchered my name mercilessly. When I got pregnant with my daughter, I considered naming her as my first act of motherhood; I could not afford to mess it up.

Black parents in the United States don’t have the luxury of naming their children thoughtlessly. By this, I mean we are not allowed to step outside the lines of normative baby names in the United States and just be whimsical. We are not called creative, but ghetto. If your child is Black with a name that will give people pause, it is no longer just a name; it is a “Black” name, with “Black” bearing a 100% negative connotation.

Worse still, studies have shown that despite diversity initiatives, hiring managers still discriminate against people with “Black” names. Kwame and Quvenzhané may be more qualified than Kevin but Kevin gets a callback more often.

Some Black parents I know approach the conundrum by giving their child as “American” a name as possible. Black children are already discriminated against by virtue of their skin color. Why exacerbate the problem with a name that denies your children an opportunity before they are able to prove themselves? I understand and respect this viewpoint, even if I disagree with it.

I knew long before my baby arrived that she would not have an English name. That, if I named her anything questionably ethnic, people would say her name with an invisible question mark at the end. Did I say this correctly? Why is your name different? Are you even from here?

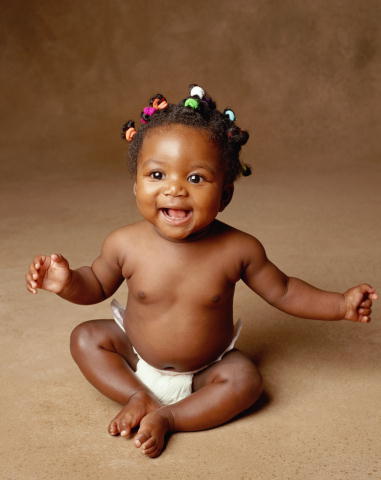

Despite all these odds, I gave my daughter the name Samira, which isn’t exactly Samantha. Here is why I gave my daughter a Black name, regardless of the stigma:

- I want her to have a name she can be proud of.

For me, this meant deliberately choosing a name that spoke to my prayers for her and a name I found beautiful. I loved the name “Samira” because it is lilting. I will teach her what her name means and encourage her to live up to it.

- I want her understand that her heritage did not begin in America.

Giving my daughter an African name is an act of cultural reclamation. My own mother named me Tafakari (to reflect) at birth and made sure I knew where my name came from. Even though we cannot pinpoint our ancestral origin, we identify Africa as the cultural home for many of our family traditions. If she struggles, as I once did, with the inevitable questions that come from being different, I will tell her: Our ancestors came from Africa. Your name honors them.

- I want her to know she is capable no matter what her name is.

We often tell Black children they must be “twice as good” to get half as far as their White counterparts. It is entirely true that one day, some recruiter may look at the name “Samira” on a resume and assume my daughter is Black. They may even pass her over. But the truth is this: had her name been Samantha or LaShawn, she would still possess the same talents. I want her to believe in her ability to succeed independently of people’s prejudice for or against her name.

- Racism doesn’t play by the rules. Black parents cannot win the respectable name game in America.

Black people are discriminated against primarily because we are Black; our names are just a scapegoat. For example, “Tyrone” has come to stand for a “stereotypical” Black man. But did you know that the name Tyrone is Irish in origin? A name doesn’t have to be “creative” or “ghetto” to be Black; it just has to be Black long enough. And as soon as we make something “Black, ” the cycle of discrimination begins afresh.

- Because we cannot beat racism by placating it, I want my daughter’s name to be a message.

My daughter is and will be her own person; she is not an activist pawn. But the America I want her to live in will have room for people of all ethnicities to exist without Anglicizing their names. Respect for diversity will not come by assuaging the prejudices of others. The more Americans we see walking around with names like Samira, the less surprise we will see on peoples’ face.

We should be able to give our children names that we love without worrying if they will be stigmatized because of it. I don’t know when that day will come. But until it does, I will continue to name my children with hope, with love, and with unabashed pride for our culture.

Dara Mathis is a freelance writer, editor, and poet who lives in Georgia with her husband and daughter. Her writing interrogates the politics of respectability for women, concepts of femininity, motherhood, and the intersection of race and gender. You can catch her tweeting reckless acts of punctuation on Twitter @dtafakari and at daratmathis.wordpress.com.